MANTEE, Utah — Garrett Clark estimates he’s spent about six years in the Sanpete County Jail, an unassuming concrete building perched on a dusty hill just outside the small rural town where he grew up.

He blames his addiction for this. He began using in middle school and became addicted to meth and heroin by adulthood. At various points, he has spent time with his mother, his father, his sister, and his younger brother.

“That’s all I’ve ever known in my entire life,” Clark, 31, said in December.

Clark was in jail to pick up his sister, who had just been released. The brothers and sisters think this time it will be different. Both of them are of calm nature. Shantel Clark, 33, completed her high school diploma during her four-month stay in prison. They have a place to live where no one is doing drugs.

And they have the county sheriff’s new community health worker, Cheryl Swap.

“He definitely saved my life,” Garrett Clark said.

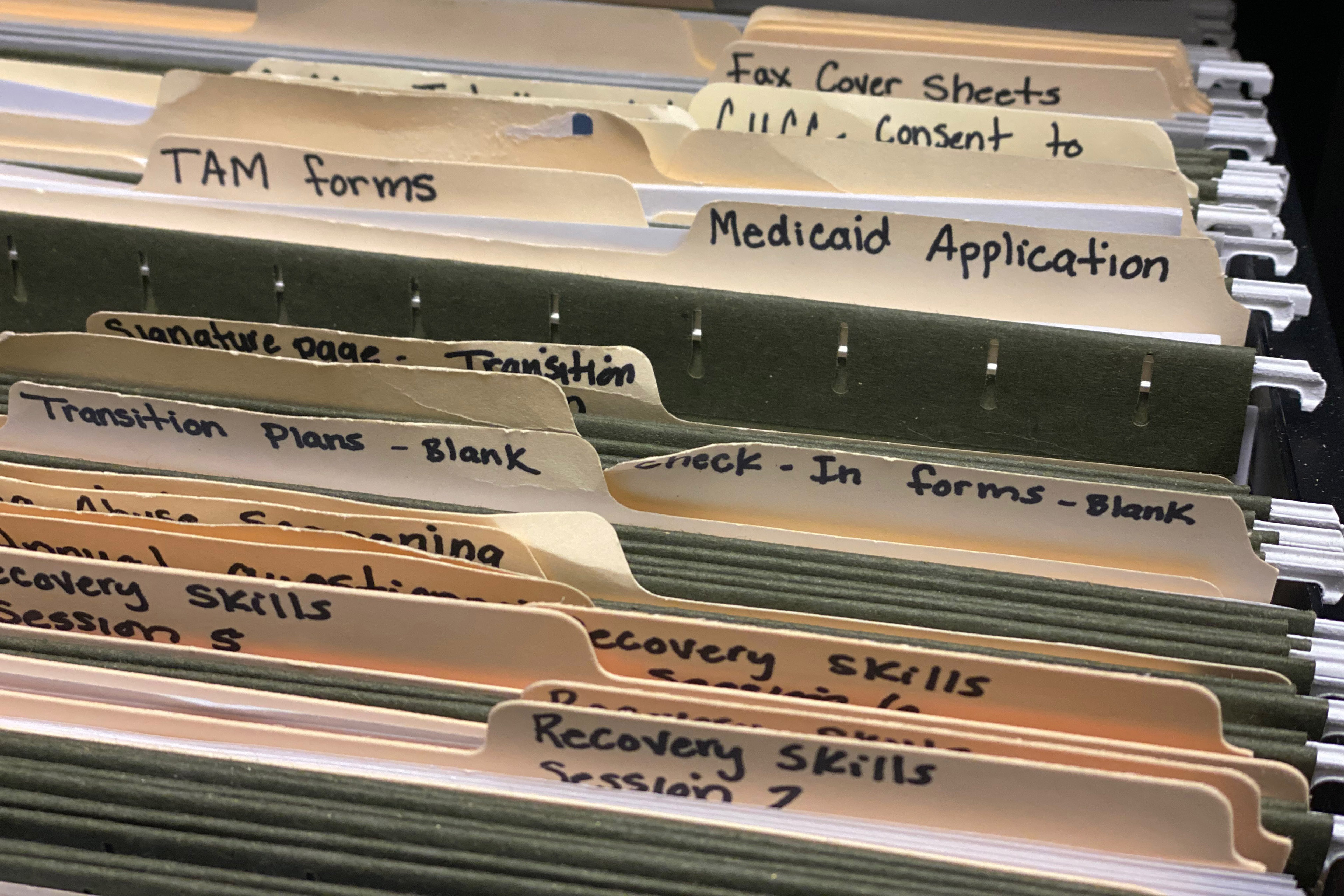

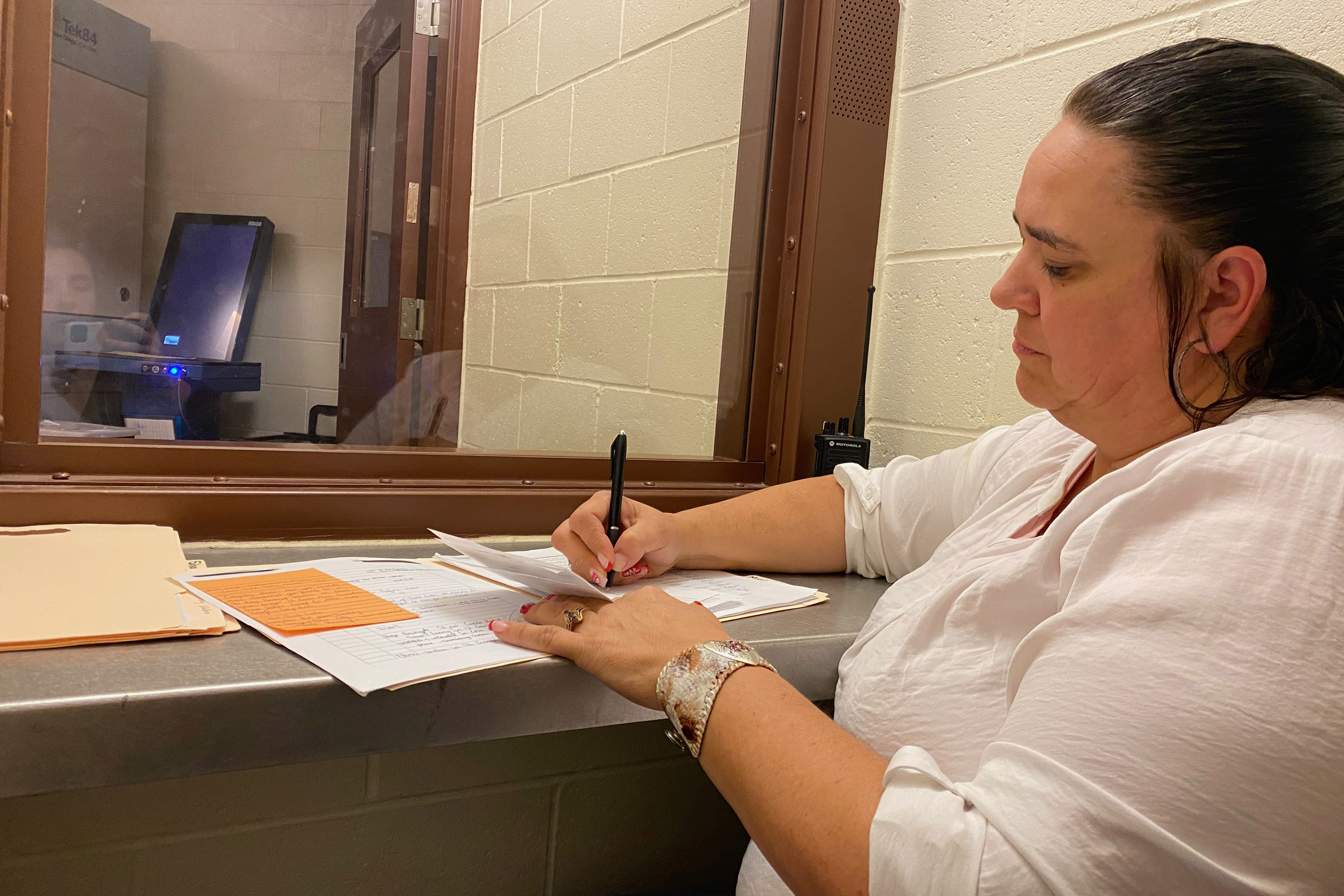

Swapp meets with each person incarcerated at the County Jail shortly after they arrive and helps them make a plan for the day they get out.

She makes sure everyone has a state ID card, a birth certificate, and a Social Security card so they can qualify for government benefits, apply for jobs, and get treatment and probation appointments . She helps almost everyone enroll in Medicaid and apply for housing benefits and food stamps. If they need medication to stay off drugs, she provides it. If they need a place to stay, she finds them a bed.

The swap then coordinates with the jail captain to release people directly to the treatment facility. No one leaves prison without a travel bag and a drawstring backpack filled with items like toothpaste, blankets, and a personal list of job opportunities.

“A missing puzzle piece,” Sgt. Gretchen Nunley, who runs educational and addiction recovery programming for the prison, called Swap.

The swap also assesses each person’s drug history, conducted by the county. More than half of the people reach jail due to some drug addiction.

At the national level, 63% people According to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the rate of people in local jails struggling with substance use disorders is at least six times higher than the general population. Federal data shows that the incidence of mental illness in prisons is more than double the rate of the general population. According to one, at least 4.9 million people are arrested and jailed every year Analysis of 2017 data By the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit organization that documents the harms of mass incarceration. The analysis found that 25% of those in prison have been booked twice or more. And of those arrested twice, more than half had a substance use disorder and a quarter had a mental illness.

“We don’t lock people up because they have diabetes or epilepsy,” said David Mahoney, a retired sheriff of Dane County, Wisconsin, who served as president. National Sheriffs Association In 2020-21. “Every community needs to ask this question: ‘Are we meeting our responsibility to each other by locking people up for a diagnosed medical condition?’”

The idea that county sheriffs could be accountable to society for providing medical and mental health treatment to people in their jails is part of a broader shift in thinking among law enforcement officials that Mahoney said he has seen during the last decade. have seen.

“Don’t we have a moral and ethical responsibility as community members to address the reasons people are coming into the criminal justice system?” asked Mahoney, who has 41 years of experience in law enforcement.

Swap previously worked as a teacher’s aide for what she calls “behaving kids” – kids who had trouble self-regulating in the classroom. She feels that her work in prison is a way to change things for the parents of those children. And it appears to be working.

Since the Sanpete County Sheriff’s Office hired Swap last year, recidivism has declined sharply. In the 18 months before she began her work, 599 of those booked into the Sanpete County Jail had been there before. In the 18 months since its launch, that number has dropped to 237.

In most places, people are released from county jails with no health care coverage, no jobs, nowhere to live, and no plan to stay off drugs or treat their mental illness. research shows People recently released from prison have a 10 times higher risk of overdose than the general public.

Sanpete was no different.

“For the seven to eight years we’ve been here, we’ve just been releasing people and keeping our fingers crossed,” said Jared Hill, Sanpete County’s clinical director and a counselor at the jail.

Nunnally, a programming sergeant, remembers seeing people released from prison walking miles into town with nothing but the clothes they were wearing on the day they were arrested – this was known as the “walk of shame”. Swap hates that phrase. He said no one has undertaken the journey on foot since it began in July 2022.

The swap’s work was initially funded by a grant from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, but it proved so popular that Sanpete County commissioners voted to use a portion of it. opioid settlement amount To cover the position in the future.

Swap does not have formal medical or social work training. She is certified by the state of Utah as a community health worker, a job that has become common across the country. According to , about 67,000 people were working as community health workers in 2022 US Bureau of Labor Statistics,

There is growing evidence that the model of training people to help their neighbors connect with government and health care services is a good one, said Aditi Vasan, a senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. who reviewed research On a relatively new role.

The day before Swap coordinated Shantel Clark’s release, she sat down with Robert Draper, a man in his 50s with long white hair and bright blue eyes. Draper has been in and out of prison for decades. He had been sober for a year and was taking care of his ailing mother. She kept getting worse. Then his daughter and her child came to help. It was all too much.

Draper said, “I thought, if I can go and get high, I can deal with this shit.” “But when you’ve been using it for 40 years, it’s easy to repurpose it.”

He said he didn’t blame his probation officer for putting him back in jail when he tested positive for drugs. But he believes going to jail is an overreaction to a recidivist. Draper sent a note to Swap via prison staff and asked to see him. He was hoping she could help him get out so he could be with his mother, who had just been sent to hospice. He missed his father’s death years earlier because he was in jail at the time.

Swap listened to Draper’s story without interruption or questions. Then she asked if she could go over her list with her so she could know what she needed.

“Do you have your Social Security card?”

“My cards?” Draper shrugged. “I know my number.”

“Your birth certificate, do you have it?”

“Yeah, I don’t know where it is.”

“Driver’s license?”

“No.”

“Was it cancelled?”

“A very, very long time ago,” Draper said. “DUI from 22 years ago. Paid for everything.”

“Are you interested in getting it back?”

“Yes!”

Swap has some version of this conversation with everyone he meets in prison. She also tells him about his history with addiction and asks him what he needs most to get back on his feet.

She told Draper she would try to get him into intensive outpatient therapy. This will involve four to five classes a week and a lot of driving. He’ll want his license back. She didn’t make any promises but said she would talk to her probation officer and the judge. She sighed and thanked him.

“I’m your biggest fan here,” Swap said. “I want you to succeed. I want you to also live with your mother.”

The federal grant funding the launch of SanPete’s Community Health Worker Program is held by Intermountain Health, a regional health care services organization. Intermountain took the idea to the county and provided support and training to the swap. Intermountain staff also administer a $1 million, three-year grant that includes efforts to increase addiction recovery services in the area.

A similarly funded program in Kentucky called First Day Forward took the community health worker model a step further, using “peer support experts”—people who have experienced the issues they are facing to help others navigate them. Trying to help. HRSA spokespeople pointed to four programs, including Utah and Kentucky, that are using their grant money to incarcerate people who have been sentenced or are serving time in local jails.

Back in Utah, Sanpete’s new prison captain, Jeff Nielsen, said people in small-town law enforcement are no different than people still serving time.

“We know these guys,” Nielsen said. He has known Robert Draper since middle school. “They are friends, neighbors, sometimes even family. We would rather help than lock them up and throw away the keys. We would like to help them give them a good life.”

rural-jails-turn-to-community-health-workers-to-help-the-newly-released-succeed-kff-health-news